Dim light spills across the shelves at blind box toy store Mindzai in Toronto, reflecting off the glassy eyes of dozens of tiny plush monsters. Some are dressed as witches, others as cowboys or pumpkins. Outside, the street bustles with traffic and chatter, but inside, a soft lo-fi playlist hums in the background. A young woman makes her way to the display case, eyes scanning for a familiar figure: wide grin, patchy fur and crooked little teeth. A Labubu! She unboxes figures in hope of finding the one she didn’t get last time.

Scenes like this have become increasingly common in metropolitan cities like Toronto, where designer toy shops have turned into quiet hubs for Gen Z collectors. At the heart of it all is Labubu, a monster elf created by Hong Kong artist Kasing Lung. “The spotlight is on him now,” says Chris Tsang, president of Mindzai Productions, a Canadian retailer and distributor specializing in designer toys, art collectibles and game studios.

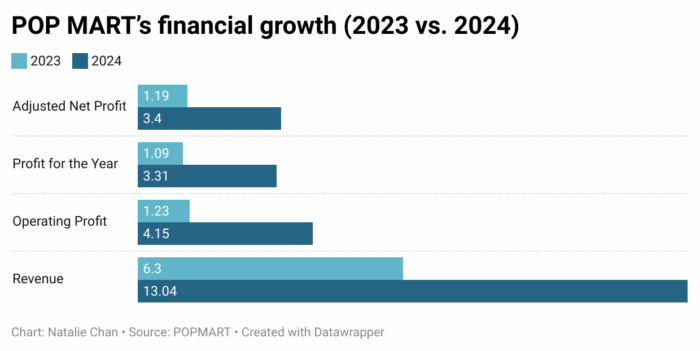

Labubu’s popularity is surging alongside Pop Mart’s global expansion. Founded in 2010, the Chinese toy company reported 132.1 per cent year-over-year growth in overseas revenue in 2023 and now operates 428 stores worldwide, according to its 2024 annual report. While Pop Mart is also known for other hit characters, like Dimoo, Skullpanda and Crybaby, Labubu has evolved into a top-tier IP and a driving force behind a cultural and commercial wave. In addition, Forbes reports that POP MART’s founder, Ning Wang, became China’s 10th richest person and gained $1.6 billion USD in wealth in 2024 alone, much of it driven by Labubu’s explosive rise.

Evidently, as blind box culture spreads across North America, the monster elf has emerged as a symbol of how Gen Z is reshaping art, retail and nostalgia all at once.

While Labubu may be today’s star, the blind box culture it represents has roots in Japanese tradition and early indie art scenes.

“Blind boxes became popular because of indie artists making their own toys in small runs,” explains Tsang. He sees Pop Mart and Labubu as simply the latest evolution of that trend.

When the culture around these toys first began spreading in North America, many customers didn’t understand the appeal. “We had a lot of complaints before, but now it’s not a thing,” he said.

For many, the mystery of which character might be in their box has become part of the ritual. “You’re buying something and you don’t even know what it is… It’s capitalizing on the most impulsive instincts of consumerism,” says Dr. Andrew O’Malley, professor of English at Toronto Metropolitan University. He linked it to the gacha machines of his childhood, those capsule toy dispensers that offered the thrill of surprise with every coin.

Unlike Gacha, the blind box concept took time to click, but today, its steady stream of new releases has kept collectors coming back. With their scruffy fur and snaggle-toothed grins, Labubu figures are weirdly adorable, the kind of ugly that’s actually kind of cute.

“It’s similar in some ways to other kinds of ugly toy phenomena from the past,” says O’Malley. For instance, Cabbage Patch Kids in the 1980s or trolls in the 2000s. On the contrary, he points out, Labubus are “not really a children’s toy…[they are] consumed primarily by people who are young adults.” Even millennials and beyond. What sets Labubu apart, however, is how the craze has crossed over into mainstream pop culture. Lisa from BLACKPINK famously sparked a surge in demand after featuring the toy on her bag, while celebrities such as Rihanna, Dua Lipa and Michelle Yeoh have been seen embracing Labubu. The trend has cut across generations and demographics, reinforcing Labubu’s global reach.

That difference points to a deeper cultural shift; this nostalgic pull and its new audience reflect a reimagining of who gets to claim childhood. O’Malley sees it as a bridge between youthful memory and adult identity. “There seems to be a collapsing of the window of nostalgia,” he says.

He explains that nostalgia, as we understand it now, began not just as a personal feeling, but as a shared cultural response to rapid change. First coined in the 1600s by a physician to describe the homesickness of Swiss soldiers, the concept later evolved into a romantic longing for an idealized past — often viewed through the lens of childhood. “It’s a cultural and social condition and phenomenon,” O’Malley says, “but it has very specific individual resonance for people experiencing it.”

While Labubu is currently capturing most of the world’s attention, Tsang points out that blind box culture didn’t start with POP MART, and it certainly won’t end there. “Every day, there’s a new one,” he says, adding that Mindzai carries countless brands, including Medicom Toy, Tokidoki and Sanrio.

One of the earliest designer toys to gain global traction was Bearbrick, a blocky art figure launched in 2001 by Japan’s Medicom Toy. While not a blind box product, Bearbrick helped popularize the idea of collecting toys as limited-edition art, paving the way for today’s explosion of collectible figures.

“The hype is still building,” Tsang says. “There will be more brands that rise and more indie artists that create their own products. The blind box market is not going to disappear anytime soon. Trading cards, blind box toys and even apparel all have a ‘blind box’ component to them.”

But for Tsang, the heart of blind box culture is not just about the hype; it’s about the artists. He believes more attention should be given to the independent designers whose stories and creativity shape the toys, rather than just the names of big brands.

In the case of Kasing Lung, Labubu was inspired by the whimsical, sometimes mischievous creatures of his childhood imagination, first brought to life in The Monsters, the fictional universe he created. Labubu wasn’t even the main character at first, he wanted to design a character that felt imperfect yet endearing, with details like its nine jagged teeth, a hidden symbol of its magical and otherworldly nature, for those who look closely.

While The Monsters features many other unique characters, Labubu’s rise has carried the spirit of the entire series to a global audience, proving that even a side character can define a brand. Now celebrating its 10th anniversary, Labubu stands as both a fan favourite and a testament to Lung’s commitment to storytelling over market trends.

Back in Mindzai, the young woman finishes unboxing her toy. The foil crackles as she tears it open. Her eyes pause. It’s a new one, unfamiliar. She turns it over in her hands, already imagining where it’ll go on her shelf. Maybe next time, she’ll get the one she’s chasing. Or maybe not. That’s the game.

Like this post? Follow The RepresentASIAN Project on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube to keep updated on the latest content.