Though many writers have come close, no combination of words can quite capture the complex and convoluted process of grieving. Grief—and grieving—to put it simply, is hard. Grief manifests in everyone differently, it can be triggered at the slightest provocation, and it rarely follows a linear timeline. The grieving process can become further complicated when one is a member of an Asian family, especially a diaspora member, because even when words aren’t dismissed in favour of actions in Asian cultures, they can be hard to formulate due to cultural and linguistic barriers.

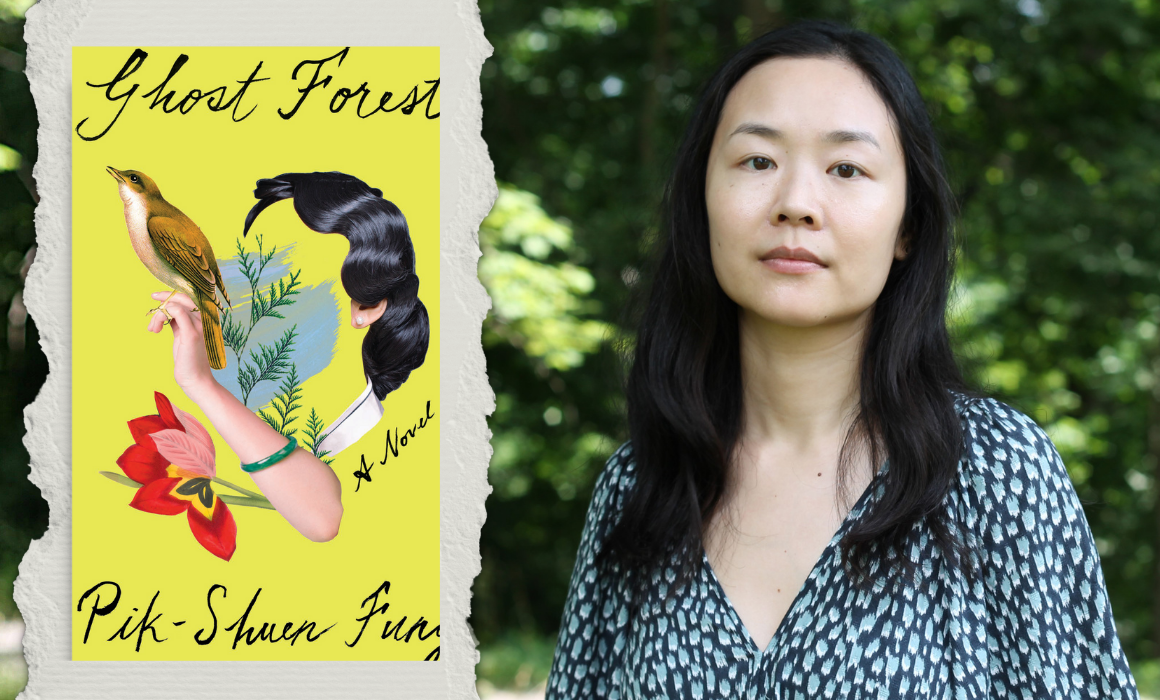

This question of how one can address grief when one’s family is reluctant to talk to each other guides Pik-Shuen Fung’s debut novel, Ghost Forest. The story follows an unnamed narrator who is grappling with her father’s death. The narrator is part of an astronaut family — her father stayed behind in Hong Kong to work while the rest of the narrator’s family immigrated to Vancouver, Canada after the 1997 Handover when the British returned Hong Kong sovereignty to China.

The narrator recalls how the physical distance between her and her father evolved into an emotional one and reconciles this distance with the grief she feels in the wake of his illness and subsequent death.

“[The book is] about grief and love and all the things we don’t say to each other in a family,” Fung tells The RepresentASIAN Project, “But it’s also about joy and [the] moments of absurd humour that we find, even in grief.”

A lot of grief in the book stems from the loss of a parent, but some of it also stems from the loss of home as an immigrant and a member of the Asian diaspora in North America. During many parts of the book, the narrator emphasizes her uncertainty over where she belongs and her envy towards those who don’t have to choose a home.

“I definitely feel a sense of loss [as a member of the Asian diaspora]. Not only a loss of my mother tongue—because I feel a lot more comfortable expressing myself in English than in Cantonese—but also it’s that feeling of not feeling really from one place or the other. It’s definitely a question that I’m asking in this novel and also I’m still in the process of asking myself. I’m not sure if there’s any way to really figure it out ever,” Fung says. “I think that the sense of rootlessness is a really big part of this book. And one of the questions that I wanted to ask is, ‘What is home, if your family is living in two different countries, if one of your parents is largely absent, and if there’s a distance that is not only geographical, but cultural?’”

Though many aspects of Ghost Forest’s narrator’s life mirror Fung’s own, the New York-based author clarifies that the book is not a memoir. “It is a book inspired by events from my life, but at this point it’s been shaped and fictionalized a lot,” she explains. “I chose to publish it as a novel instead of a memoir because I wanted that freedom to change things and make things up.”

“I definitely feel a sense of loss [as a member of the Asian diaspora]. Not only a loss of my mother tongue—because I feel a lot more comfortable expressing myself in English than in Cantonese—but also it’s that feeling of not feeling really from one place or the other.”

The first thing that strikes the reader about Ghost Forest is the large expanse of space present throughout the book, both visual and rhetorical. The protagonist narrates her story a collection of vignettes—many of which are barely a page long written in short, succinct, poetic sentences. The structure of the book almost resembles Xieyi paintings, a Chinese ink painting style that was increasingly practised by scholars after the Song dynasty and consist of artists leaving large areas of the paper blank because they felt that absence was as important as presence.

Fung has similarly left many areas of the book blank, both by leaving things out and spacing things out via paragraph and chapter breaks. “I wanted to create a sense of spaciousness and a space for the reader to be able to enter the book and bring their own experiences and their own emotions. So, thinking about what I wasn’t saying was one part of it and also showing a lot of space visually was another part of it,” she says. “I [also] omitted a lot of things, because I wanted to capture this experience of being inside this family that doesn’t talk about so many different topics,” she adds.

The family in question belongs to the narrator of Ghost Forest; its members often prioritize actions over conversations, especially when it comes to topics of absence, loss, and the ensuing grief, an experience many readers can relate to. The narrator’s experience might especially resonate with readers from Asian families—especially if they are a diaspora member—since actions often take precedence over words in many Asian cultures, making it hard to talk about difficult topics, including (but not limited to) grief and loss. And even when words aren’t dismissed in lieu of actions, they can still be hard to formulate due to cultural and linguistic barriers.

“One of the questions I wanted to ask is, ‘What is home, if your family is living in two different countries, if one of your parents is largely absent, and if there’s a distance that is not only geographical, but cultural?'”

How one can address grief when one’s family is reluctant to talk to each other is the guiding question behind Ghost Forest and its narrator partially answers this question by, well, talking. The narrator’s anecdotes and observations are interspersed with first-hand accounts from her mother and grandmother about their own lives, inspired by real-life conversations Fung had with her mother and grandmother.

“I was surprised that they really enjoyed sharing their stories with me. And I realized that ‘Oh, I probably never truly listened to my mom in that way before, not for such long stretches,’” Fung says. “In the end, that was a really meaningful part of the process. I feel like I know them better and what they’ve been through, so I can relate to them more.”

“There were definitely certain points when I was talking to my mom and grandma when they would say certain words and I’d be like, “Okay, wait, what’s that word?” And then, I’d ask my mom to WhatsApp me the character so I can look it up,” she admits. “But I wasn’t really talking to them about philosophy or any academic topics. So [the language barrier] came up once in a while, but it wasn’t a recurring issue that I faced.”

Despite Ghost Forest’s protagonist navigating grief through words, Fung doesn’t want to prescribe readers a way to cope with grief but rather encourage them to find their own answers through her book.

“I think everyone has their own way [of grieving] and I don’t think any way is correct or better than others. That’s why I wanted to create so much room in the way that I wrote the book,” she shares. “It was really important for me not to guide the reader towards any specific messages or conclusions, but instead, my big wish was to create a space for others to grieve and bring their own lives into the book.”

Ghost Forest is available now in bookstores nationwide.