‘My Parents Own the Chinese Restaurant’: An Excerpt from Rachel Phan’s Debut Memoir ‘Restaurant Kid’

“Like so many other Chinese families who have settled in small towns across Canada, our path toward the elusive Canadian Dream would begin with a family-owned business.”

The author and her family. Photo Courtesy Rachel Phan.

Rachel Phan is a Chinese Canadian bestselling author and journalist based in Toronto whose work blends sharp cultural insight with heartfelt personal storytelling. Her debut memoir, Restaurant Kid: A Memoir of Family and Belonging, is a powerful exploration of growing up in the shadow of her family’s Chinese restaurant, run by her Vietnamese refugee parents in a small town in Southern Ontario. Feeling lost and often lonely, she turned to writing as a form of escape, dreaming up stories where girls like her could take center stage.

Through Restaurant Kid, Phan explores themes of identity, assimilation, racism, and belonging, using her own coming-of-age story to reflect on broader issues faced by children of immigrants and refugees. Phan’s voice, at once humorous, vulnerable, and fiercely honest, has struck a chord with readers across the country, quickly making the memoir a national bestseller and earning praise for its powerful blend of personal storytelling and cultural critique.

Following the breakout success, Phan is now working on her second book, That Asian Girl Is a Problem slated for release in fall 2026. The upcoming essay collection will continue her exploration of race, gender and identity, diving into how racialized women are made to feel like they are “a problem” in various facets of life, including work, relationships, and even their own bodies. With her signature mix of memoir, cultural critique, and unfiltered honesty, Phan’s second book is set to be as compelling and thought-provoking as her first.

Below, an excerpt from pages 1-5 of Restaurant Kid: A Memoir of Family and Belonging, by Rachel Phan ©, (Douglas & McIntyre, 2025). Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

“My Parents Own the Chinese Restaurant.”

I am three years old when I meet my replacement.

Instead of a squirmy, red-faced little thing, what comes to consume my parents’ already scarce time and attention is a quaint red-bricked building in Kingsville, Ontario—a small town where the people are as friendly as they are pale.

It’s a blazingly sunny day in 1991, and our family of five has just pulled up to the back of that red-bricked building in our trusty red Chevrolet Lumina. I remember straining my short neck to look up at this unassuming place my parents kept saying we would make our own.

Like so many other Chinese families who have settled in small towns across Canada, our path toward the elusive Canadian Dream would begin with a family-owned business. This building would be transformed from a generic coffee shop into a humble restaurant serving Chinese Canadian cuisine, with my parents at the helm.

To stake their claim on this building, my parents bestow a name upon it. My name. At birth, I was christened Rachel—the Anglo name on my government documents—but to my family, I’ve always been little May May. In Chinese, may or mei can mean “beautiful” or “bright” or “reliant” or even “Chinese plum.” It is a name that takes on different meanings and significances depending on the tone, context, and intentions of the speaker.

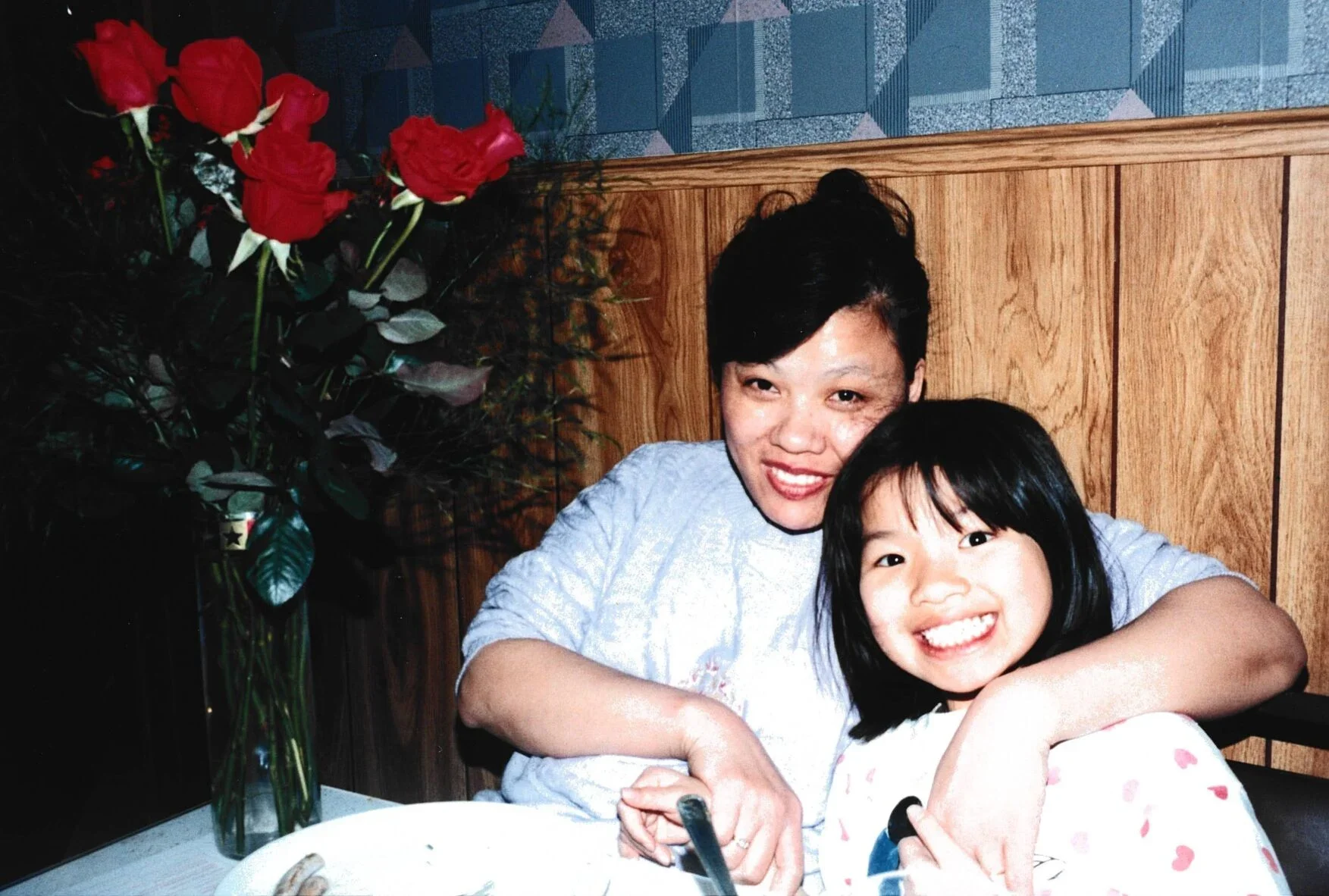

Rachel Phan and her mother. Courtesy Rachel Phan.

With such stunning versatility and range, it seemed a natural fit for my parents to name this new building, this new adventure, this new evidence that they’d finally succeeded in Canada, after me, their youngest child.

They name it the May May Inn.

“What do you think, May May?” My dad crouches down low to meet my eyes. My older brother, John, who is ten, grumbles behind him in typical middle-child fashion, envious that it is my name emblazoned on the restaurant. (“How come you named the restaurant after her? Can you name a dish on the menu ‘John’s jumbo shrimp’?”)

It is a monumental day. The turning point for our family. Finally, my parents have something that is all theirs. They can be their own bosses, set their own hours, make even more money. For two kids who survived bombs and starvation during a pointless war in Vietnam, it is a dream come true.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that unassuming red-bricked building would become my parents’ new baby. I was no longer the only May May in their lives. From that day on, I am a restaurant kid.

The restaurant becomes ours ten years after my parents landed in Canada in 1981, with their infant daughter, Linh, in tow and an unborn baby the size of a plum—my brother, John—in my mother’s womb. They finally have a home after two years of waiting in a Hong Kong refugee camp, where my parents landed after fleeing postwar Vietnam on a too-packed boat of disease and despair.

Rachel Phan and her parents. Courtesy Rachel Phan.

When they land in Quebec, it is a characteristically cold February day. They marvel and shiver at the sight of the unfamiliar white powder that covers everything they see. It is so completely different from Hải Phòng, where they were born. It terrifies them.

“I had tears in my eyes,” my dad remembers. “I thought, ‘What the hell? We came to Canada and it’s all this? It’s all white.’” A thousand questions race through Dad’s head upon landing in this new place they were to call home. How do people live here? How do people work? What are we going to eat? But my dad keeps his anxious thoughts to himself. My parents both speak Cantonese and Vietnamese, my dad can understand Mandarin and some Japanese, but neither know English when they arrive in their new country. What choice do they have but to stay quiet? What choice do they have but to parrot back the same strange words they hear from the same strange people handing them their first-ever winter boots and jackets?

“Snow,” someone says, catching the way my parents’ wide eyes survey the shockingly white landscape before them.

“Snow,” they repeat, feeling how the word wraps heavy and confusing around their tongues.

According to their official landing document, my parents are stateless and the amount of money they had to transfer to Canada was “nil.” They have not a single cent to their names and no other home to speak of that would claim them. Canada would be their saviour, their great hope, their land of possibilities. My dad is twenty-two years old and my mother nineteen—just two young, immature kids already parents to a fourteen-month-old daughter, with another child on the way. They are overwhelmed and frightened.

Rachel Phan and her brother. Courtesy Rachel Phan

My parents settle in a small town in southern Ontario called Leamington, also known as the “Tomato Capital of Canada” because of its produce-rich greenhouses and the Heinz factory that made the town smell like ketchup chips on windy days. My mum’s eldest brother had settled there six months before my parents’ arrival.

After the first night in their government-provided apartment, my parents’ collective anxieties ramp up to eleven when they discover their front door frozen shut by a particularly nasty overnight snowstorm. “It’s like being in jail!” my parents wail, their hearts and bodies longing for humid, familiar Vietnam.

Things don’t get much better from there. Following their arrival, my parents pick up odd jobs that no one else seems to want. My mother gets a job sorting through and cutting manure-covered fungi at the mushroom farm, whereas my dad gets a job picking tomatoes and beans. Soon, the days and weeks and years start to quickly blend together—a mix of social assistance, sponsored church visits that end the moment my parents get too busy, and long hours of menial labour.

“Even though we were struggling, we felt really happy,” Dad says, a faraway look in his eyes. “We came from a country with war, but Canada was peaceful. We weren’t scared of bombs or guns here. Even though we were poor, we were still happy.”

Three years after landing, something life-changing happens to Dad: he sees another Chinese person in Canada who miraculously isn’t related to him or my mum. Elated by the familiar set of this man’s eyes and tanned skin that mirrors his own, Dad goes up to this stranger who, to his immense delight, also speaks Cantonese. What luck! The man, Howard, tells Dad that he owns a Chinese restaurant in town called Happy In. Dad, sensing this was his chance to pivot from back-breaking farm work to back-breaking restaurant work, takes his shot. This way, he’d at least be around other Chinese people.

Rachel Phan. Courtesy Rachel Phan.

“Are you hiring?” he asks before the two part ways. He is hired on the spot, becoming Happy In’s newest cook.

Dad has to learn everything when he starts his new job because the food he is responsible for making is as foreign to him as it is exotic to the customers. Dishes like the elegantly named “chicken balls,” which are chunks of chicken cocooned inside deep-fried breading and smothered in a violently red sweet-and-sour sauce, are so unlike the braised meats, steamed fish, and stir-fried dishes my family eats. There are so many dishes to learn, including more deep-fried fare like chicken soo guy and lemon chicken. My dad, who grew up impoverished and hungry in Hải Phòng, is given a wok and a trial by fire. Over time, he learns that chow mein is a popular, watery dish made of bean sprouts, though Cantonese chow mein is a crispy noodle dish with vibrant green vegetables and sauce-slicked pork, chicken, and shrimp. He also discovers that restaurant work, though a different kind of grind than greenhouse work, is a grind on his body all the same. At the restaurant, he works six days a week, ten hours a day. For his labour, he is paid $180 every week.

With Mum making a similar amount and two young children to feed, clothe, and shelter—I wouldn’t arrive for another four years—my dad picks up part-time seasonal work as a worm picker between April and June. During these months, he works at the Happy In until 2 a.m. and then heads over to the manure-rich land outside the mushroom farm where Mum works. There, he trawls through dirt and soil in the dead of night in search of worms to sell as fishing bait or super-secret ingredients in beauty creams. He is paid $30 for each full pail—in reality, old Heinz ketchup cans. On his first night, the ground surges and crawls with moving worms. Dad, scared but brave, grabs them by the handful and fills seven cans with their squirming bodies. At the end of his shift, when he gets his $210 in cash—under the table so he doesn’t get taxed—it is like striking gold. The overflow of bills in his pocket makes his fifteen-hour workday and subsequent trek home at 6 a.m. bearable. Once at home, with the early dawn breaking outside, he catches what little rest he can before he is back in the restaurant kitchen again.

Restaurant Kid: A Memoir of Family and Belonging is available now wherever you buy books.