In 2006, just after Hurricane Katrina ravaged its way through New Orleans, 500 Indian welders and pipe fitters were lured to the U.S. Gulf Coast to rebuild oil rigs in exchange for green cards. They were each convinced to spend thousands of dollars to make their way there, plunging themselves and their families into crushing debt. While they had expected to live out the American Dream, instead, they would spend years living and working in squalid conditions, and fighting to be paid what they were owed. It would become one of the largest human trafficking schemes in U.S. history.

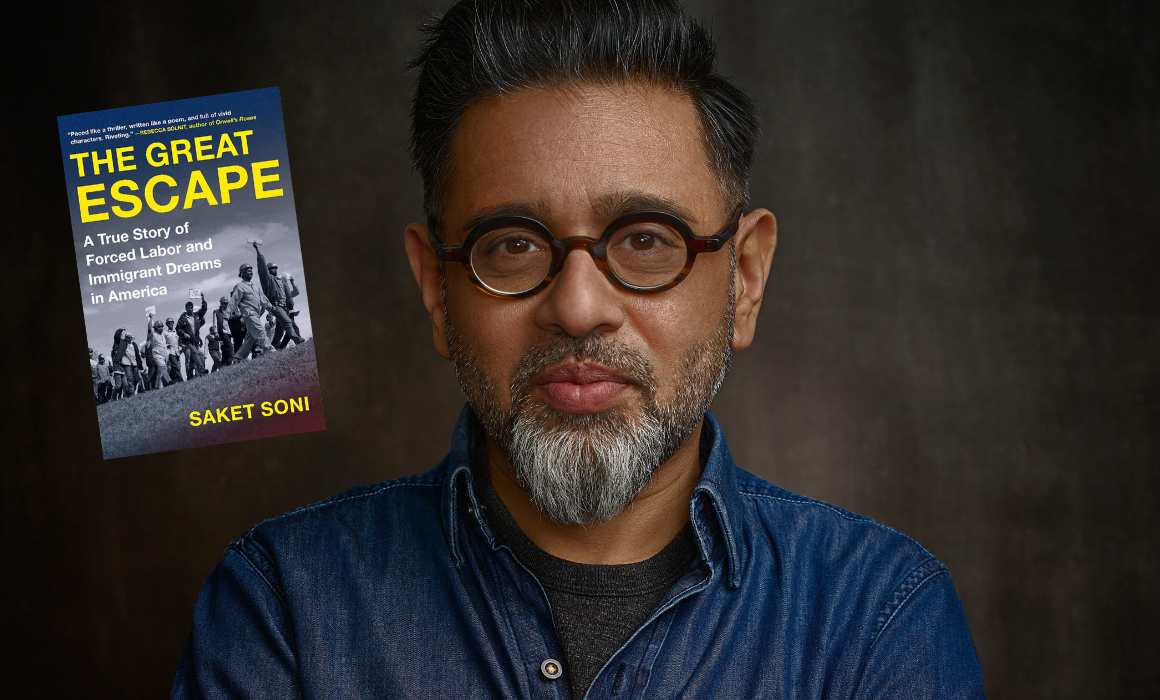

Saket Soni, a New Orleans-based labour organizer and human rights strategist, learned about the situation when, one midnight, he received a phone call from one of those very labourers. Over the next several years, he assisted the exploited workers in escaping their labour camp, fighting the system (specifically, Signal International, the company that used lofty promises to bring these men to the U.S.), marching for their rights, and winning the visas they were long owed.

As he writes in The Great Escape, his new book chronicling their battle, “Our journey had started with a human trafficking complaint from as emblematic a place as possible: a labour camp in Mississippi. We triggered a DOJ (Department of Justice) investigation into Signal International and its network of recruiters. But ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) had wrested control of it. In their hands, it was a gun trained at the workers. ICE’s endgame wasn’t simply denying the T visas — they intended to blast the workers into oblivion.”

It’s a harrowing, gripping journey, and not an easy — but certainly necessary — read. Still, it’s nothing new for Soni, who is also the founder and director of Resilience Force, an organization dedicated to transforming America’s response to natural disasters by strengthening and securing the country’s resilience workforce.

In a conversation with RepresentASIAN Project, Soni shared how he found the trust of these labourers to share what they went through, and why their story isn’t all that new or unique, and demands to be told.

What was your goal with The Great Escape? There’s a lot to take away from your book, but was there one overall message you were hoping to convey?

I wanted to do justice to the extraordinary journey these men went on. To do that, I had to rescue them from a stereotypical “immigration story,” and recast them as the protagonists of a non-fiction thriller. That’s why the book draws on detective novels, heist films, and even great TV. I was open to any model that would help me live up to the excitement of the story.

What motivated you to put this journey to paper?

More than anything, it was the bravery the men and their families showed over their years-long freedom journey. In the writing of the book, it was friendship and food! I spent hundreds of hours in conversations with these men, revisiting some of the hardest moments in our lives in these conversations, but always over amazing meals. There are many great food moments in the book, and there were many more between us in the writing of the book.

As a labour organizer, and in your efforts to help these Indian workers get what they were owed, you walked a hard and painful road. What inspired you to take on this line of work and this fight?

I originally came to the U.S. from India to study theatre at the University of Chicago. Then I missed an immigration deadline and found myself out of status during 9/11. Overnight, like many immigrants, I lost my foothold in normal American life. That experience turned me from theatre to community organizing. My real education as an organizer came when I went down to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Black and brown reconstruction workers would gather to seek work in the shadow of a 60-foot-tall statue of [Confederate general] Robert E. Lee. I co-founded a labour rights organization that did what it could to support them. And that’s when I got the midnight phone call that put me on the trail of what would turn out to be one of the largest cases of forced labour in modern U.S. history.

You start this book by sharing a little about some of these workers’ romantic lives. Why is it necessary that, as readers, we understand what motivated them in this way, and what was at stake?

Every immigration story is a love story. One character in the book, Aby Raju, says it best: “You leave the ones you love to help them live.” He resists an arranged marriage, then falls in love with his bride-to-be over a phone call — then struggles to tell her he has to leave for America the week after the wedding! I wanted to show the full lives that Aby and other characters left in India to pursue an American promise. Then I wanted to show that much of what they were fighting for was to reunite with those they loved. The immigrant stories we tell in America often begin with the arrival in America, but there’s so much more to tell than that.

You’re careful to note the illegal fees these people were charged to work in America, and how much of a toll that took on them. Why?

These 500 Indian labourers were lured to the U.S. on promises of good work and green cards, and convinced to pay $20,000 apiece to come rebuild storm-damaged oil rigs in U.S. Gulf Coast. In India, $20,000 represents generations’ worth of savings. Many men had to sell family homes or borrow from violent loan sharks to raise that amount. The crushing debt they took on is part of what trapped them in the atrocious working conditions they arrived into: they were desperate to earn back that money.

The state of the labour camp in Mississippi was horrific, as is the toll it took on these men once they arrived. Was what you saw there unprecedented?

The conditions were truly atrocious. They lived 24 men to a trailer in a company “man camp” built above a toxic waste dump. They were fed frozen rice and moldy bread. But some of the biggest indignities were things I only understood when I got to know the workers better. For Aby, for instance, it was the day when he was 20 feet up doing a dangerous welding job on an elevated platform. He got a phone call from his pregnant wife in India, 10,000 miles away, as she was going into emergency surgery to give birth. Not only could he not be with her, he wouldn’t even get to see the son that was born that day in person for years. Each of these workers had a moment like this that ultimately made them decide to take the risk of joining our movement to escape the company and go public.

And when you witness conditions like these, how do you personally feel an employer like Signal views these men — as cattle, slave workers, objects? What are they reduced to in order to be seen as nothing more than labourers?

Some Signal managers would refer to the men by their employee numbers, and that’s all they saw them as. Fascinatingly, the guards at the Signal “man camps” were often as demoralized as the Indian men were, and some wound up forming bonds with them that nobody expected.

The escape itself was arduous, and “winning” what these men did makes for a hell of an ending. Do you feel this result you all worked so hard for has had an impact? Has it been seen and heard?

The response to the book has been incredible, which is particularly exciting because it means more people than ever are encountering the men’s story. But the most important outcome of their journey was that these workers finally won the right to stay in the U.S., reunite with their families, and start new American lives.

How do you define “the resilience workforce”? Why are so many who are part of it afraid to be open about the abuses they face or have faced?

Resilience workers are America’s white blood cells — the workforce that helps America recover after climate disasters like hurricanes, floods, and fires. Many of them are undocumented immigrants, which means they’re vulnerable to severe labour abuse and life-threatening conditions. Bad contractors use the threat of deportation to keep workers trapped in ways that parallel the situation of the Indian workers in The Great Escape. I co-founded Resilience Force to be the voice for these workers, to help build them into the strong, stable, permanent recovery and preparation corps America needs.

How did you win the trust of these men? And, in writing this book, how did you win their approval to share their stories?

There was a crucial moment during our campaign when I could only win the men’s trust by opening up to them in ways I had been afraid to, sharing my own story and my own vulnerabilities with them. At that point in my life, as a 20-something labour organizer, I had cut myself off from my Indian roots. I never called my parents in Delhi. I thought of myself as an American in all but passport. The last people in the world I expected to wind up at the centre of my life were a group of Indian men trapped in Mississippi. But over the course of the journey, we formed some of the deepest bonds of my life.

You note the influence of Black labour organizers. How have they been a key influence for all organizers of colour, and why was it important to highlight this?

Early on in my time as a community organizer in post-Katrina New Orleans, I had the extraordinary privilege of being mentored by African American civil rights leaders like John O’Neal, Hollis Watkins, and Nelson Johnson. They not only taught me the craft of organizing, but also allowed me to understand America as they saw it. Early on in the Indian workers’ fight, I understood that they needed to relate those civil rights struggles themselves — to see that this country can fulfill the extraordinary promises it makes, but only through a fight. So part of the workers’ freedom journey was about connecting them to that tradition, and to those men themselves.

We saw very similar exploitation go down at the World Cup earlier this year, which took advantage of countless South Asian workers looking to support their families back home. Are incidents like this becoming more common, or is it just that they’re receiving more of a spotlight? Certainly, as the climate crisis worsens, forced labour after natural disasters is growing. How do we work against this?

Captive labour is a story as old as America, and climate resilience workers face unique vulnerabilities and deep exploitation, as I mentioned. But disaster-struck communities depend so deeply on these workers, that there’s a unique opening in these moments, points of contact between immigrant resilience workers, residents, and local political leaders that is like few things in American life. Again and again, I’ve seen how resilience work can wind up not just building infrastructure, but building friendships across America’s deepest divides — lines of race, class, immigration status, and political affiliation. I’ve seen this transform whole communities. As the climate crisis grows, these points of contact will increase, as will the opportunity to build on them.

How do you define the American Dream today? And is it something you still believe immigrants can and should aspire to?

America is facing enormous challenges right now, and freedom here has never come without a fight. But it remains a country where millions of strivers want to come to make a better life for themselves and their families. Just days ago, one of the men from the book, Shawkat Ali Sheikh, called me to share the news that his daughter — [whom] he had to leave many years ago when she was still a small girl — had been accepted into five U.S. medical schools. It shouldn’t have taken a years-long freedom fight for him to put her in the position to fulfill a dream like that, but it’s a profoundly beautiful thing that his American journey made that possible.

The Great Escape is available now wherever books are sold.

Like this post? Follow The RepresentASIAN Project on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube to keep updated on the latest content.