As South Asian Fashion’s Popularity is Rising, So is South Asian Hate

With anti-Indian racism at an all-time high across North America, the continuous co-opting of South Asian style on social media and runways isn’t just bad taste, it’s another act of hate.

Photo-Illustration by RepresentASIAN Project. Photos: Tory Burch, WWD, Gilbert Flores, Reuters, The Zoe Report, CTV News, ELLE, Stop AAPI Hate.

Another day on the internet means, at least as of late, yet another instance of white people trying to claim Desi style as their own.

In late June, Italian fashion house Prada sent models down the catwalk at its Milan Menswear Spring/Summer show in a pair of very familiar-looking braided open-toed leather sandals. While initially uncredited, as many eagle-eyed artisans noted, the sandals were pretty much a copy and paste of Kolhapuri slippers, hand-made in India and which date back to the 12th century. Earlier that month, a mirrored maxi dress from American designer Tory Burch also started making the rounds on social media, donned by several fashion influencers before quickly being heralded as “the dress of the summer.” (It should be noted that said influencers were all white).

•Tory Burch’s viral mirror dress draws attention to India’s traditional sheesha work, raising questions on credit,

— ZIN... (@Ram_Zin_) July 15, 2025

Luxury brands need to stop stealing crafts from Indian artisans without naming them. That Tory Burch mirror dress? Straight outta Gujarat& rajasthan. #indiandress pic.twitter.com/xU1sEwe6GS

The thing is, this design from Tory Burch isn’t entirely original. As some internet users quickly clocked, the design isn’t “retro” or “60’s-inspired,” but entirely emulative of sheesha, a centuries-old method of embroidery that hails from India and has been seen on aunties, didis and Bollywood stars like Madhuri Dixit and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan in Devdas. While Burch herself has noted that she takes inspiration from Indian fashion, acknowledging that the mirrored dress is crafted in India, amid the hubbub of social media circulation, that context has been completely lost and the dress’s true history devoid of meaning.

And this is far from the first time this has happened in relation to South Asian fashion. In May of last year, TikTok blew up with the #VeryEuropeanOOTD trend after fashion rental company Bipty posted a video calling South Asian-inspired attire “very European.” And in April of this year, influencer Devon Lee Carlson released a much-talked-about collection with Reformation featuring a neck scarf. Largely referred to as “vintage-inspired” by a portion of the internet, South Asian users quickly identified its true name—dupatta or chunni. Which is all to say that none of this is very new, but it is super tiring.

Something that is new, or at least worth considering? The fact that this continual co-opting is happening at a time when anti-Indian sentiment and hate is at an all-time high—and growing—across Canada and the U.S.

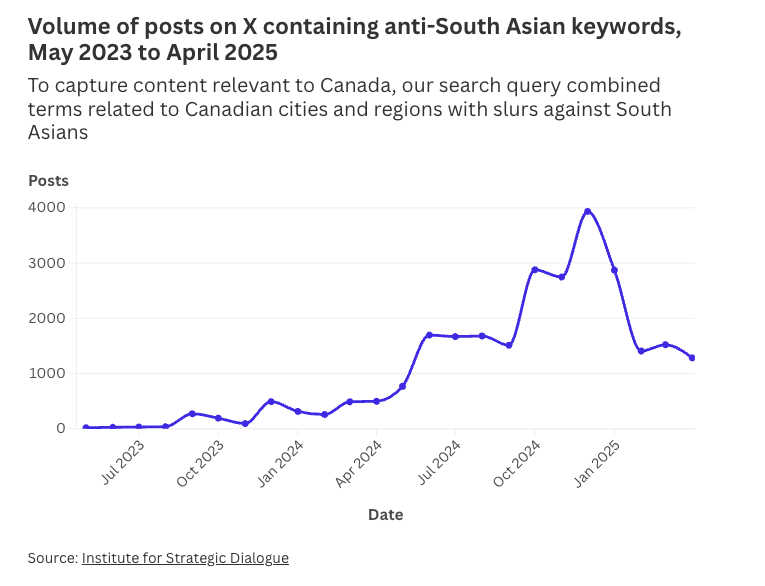

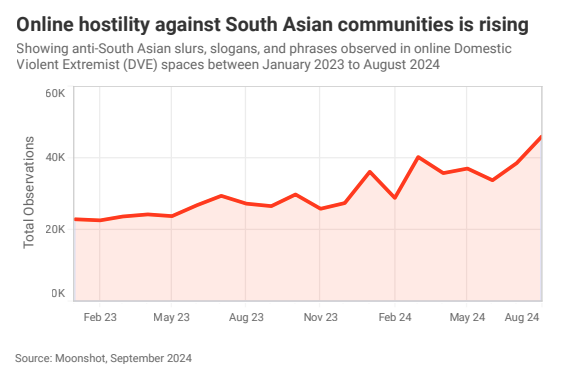

Just look at the stats. In 2023, 44.5 per cent of hate incidents in Canada were motivated by race or ethnicity, with South Asian and Black Canadians facing higher rates of hate threats and assaults. Recent research from the Canadian Race Relations Foundation also found that, between 2019 and 2022, hate crimes against South Asians increased by 143 per cent, with a quarter of South Asian Canadians reporting having experienced discrimination or harassment in 2022.

A large majority of these instances of hate are occurring online. A 2024 study from Stop AAPI Hate, a U.S.-based organization that fights hate against AAPI communities, found that between January 2024 and August 2024, anti-South Asian slurs in extremist online spaces doubled. And chances are you’ve seen it.

Anecdotally, we only have to look so far as our TikTok FYPs, which have become populated with hate-filled videos featuring TikTok users, complaining about cultural celebrations, claiming their presence means this “isn’t Canada anymore,” or fabricating untrue stories about South Asian Canadians defecating on public beaches (yes, this was really a thing).

@nnaoma_23 Indians are take over Toronto

♬ original sound - Greaze

But really none of this should come as a surprise. Because, as others online have pointed out, and as anyone who’s non-white intrinsically knows, Canada has a long history of blaming vulnerable minorities for its issues.

“Canada is a settler colonial nation, so its whole foundation is predicated on racial violence; first against Indigenous people, and then against people who provided labour for building Canada,” says Reena Kukreja, an associate professor of global development studies at Queen’s University. This started all the way back with the treatment of Chinese immigrants who came to Canada and built it from scratch via the railroad; through to the 1910s and the barring of British Indian subjects from entering the country; to Japanese Canadians who were interned in camps during WWII.

“Each epoch brings different racial groups and different discourses,” Kukreja adds. And, most importantly, “the state is directly contributing to this form of hate,” she says. “It’s not as if it is absent from this discourse; it is totally embedded in the creation and the enabling of racial violence.”

@905otlive The hate is actual crazy atp #brown #southasian #canada #fyp #foryoupage #905ot #viral ♬ original sound - 👾Will0W👾

The latest iteration of this hate stems directly from the Canadian government’s decisions around immigration; specifically, their penchant for wooing international students from countries like India (as of 2024, the Canadian government has enacted stricter requirements and put a cap on immigration numbers).

“The state knows exactly which demographics are coming to Canada because the state is the authority that gives clearance via student visas,” Kukreja says. “So they cannot say, ‘suddenly we have a problem on our hands.’ … In certain metropolises or regions, [certain demographics] become hyper-visible. That then leads to the feeling that, ‘oh, these guys are taking away our jobs, they’re taking away our housing.’” Nevermind the fact that the housing crisis in Canada precedes COVID-19 by several years. The real problem, Kukreja adds, “is that you’re encouraging this high rise in population growth without a corresponding rise in social services. So obviously it’s going to create a crisis.”

Coupled with the rise of social media, which circulates this hate in a new and unique way, “it creates anxiety [for racialized people] about where next is racial hate coming from? Will it manifest itself through comments or will it take the form of anger? …All of these then feed into one psyche and create anxiety and mental stress,” Kukreja says.

Not to mention it fosters a feeling of unbelonging, and reinforces the idea—intentional or not—that we’re legitimizing and still putting stock into racial hierarchies.

@tahalikesyou it’s gotten out of hand and acc isn’t funny tbh

♬ original sound - TAHA

For Souzeina Mushtaq, assistant professor of journalism and gender studies at the University of Wisconsin—River Falls, the continual appropriation of Desi fashion functions in much the same way. She explains, “Cultural appropriation and this rise of anti-India or anti-South Asian racism, they’re basically two sides of the same coin.”

While some might see the co-opting of saris and lehengas as harmless—or, even worse, as a twisted compliment of some sorts—the reality is, they’re not and they operate within the same system by simultaneously devaluing the people while commodifying the culture. “You are fetishizing and you’re exoticizing a culture while you’re mocking the [same] people for having an accent,” Mushtaq says. (This applies to fashion but also in other realms, like a love for some cheeky Indian takeout, all while simultaneously complaining that South Asian people smell like curry, a common stereotype).

“Cultural appropriation and this rise of anti-India or anti-South Asian racism, they’re basically two sides of the same coin.”

We’ve seen this time and time again when it comes to fashion across the board; the reinforcement that cultural clothing or customs are only “chic” when removed from the bodies and its people of origin to a (typically) white body (think Gwen Stefani’s ‘90s love for bindis, Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw wearing turbans on vacation to the middle east, and brands like H&M releasing a set that looks eerily like a shalwar kameez).

American singer Gwen Stefani attends the 1997 Billboard Music Awards. (Photo by Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

“If a South Asian woman wears a sari to work, then it’s a problem because it’s not seen as professional enough,” Mushtaq says. “But that same sari ends up on a runway or a fashion blog with zero context [and is deemed fashionable].”

In other words, regardless of whether or not designers like Burch claim their “inspiration” from Indian artisans and techniques, by removing the cultural context and presenting these designs independent of and without their cultural meaning, that meaning is essentially erased.

Take, for instance, the recent release of the “Indian Souvenir Bag” at retailer Nordstrom. Typically used to carry rice, the bags— from Japanese company PUEBCO and featuring Hindi phrases—retailed for $48USD (they’re currently sold out online), marketed as “a must-have for any traveler or lover of Indian culture.” The fact that the listing is devoid of any actual information about the culture people should be appreciating doesn’t seem to matter.

The Puebco “Indian Souvenir Bag” sold at Nordstrom.

But, as Mushtaq says, intent does actually matter. She explains, “When you’re not collaborating with South Asian designers, when you are not learning the meaning behind what you’re wearing, or even aware of the power dynamics at play, it’s problematic because it’s not about gatekeeping and you’re not taking accountability for your actions. It’s about honouring a culture, not just consuming it. You’re basically turning something which is very meaningful [into] a trend to match with the current vibe.”

The problem is that trends, vibes, looks of the moment are all passing; as is interest in them. By diminishing South Asian people and culture to these fabrics and aesthetics, it enforces the message that they themselves are disposable—which feels pretty par for the course with the current climate.

For Mushtaq, the most frustrating aspect of these conversations is that they continue to happen at all, even as we as a society continue to boast about how progressive and forward-thinking we are when it comes to sustainability or sourcing. “You have all the information available to you at your fingertips, but here is this refusal in some form to engage with the politics of fashion; who does this belong to? Why am I drawn to this look? How is it sourced?,” Mushtaq says.

But really, that way of thinking and refusal to engage deeper shouldn’t come as a surprise, and it definitely doesn’t to anyone who’s had the experience of growing up or existing in Canadian society in a body that isn’t white. Because as much as Canadians are known for being multicultural and kill-’em-with-kindness sweet, it’s all conditional and comes with specific terms for those of us who don’t fit the backwards image of what a true Canadian looks like (if you’ve ever been asked “no, but where are you really from?,” then you know that we’re talking about). It’s a hypocrisy that’s not only harmful, but straight-up infuriating.

For any change to happen, both Kukreja and Mushtaq agree that people have to actively work to unlearn their understanding of systemic power imbalances. “You’re talking about an attitudinal shift in terms of ideologies and how power is held,” Kukreja says. “…Until people resist and push back, nothing will happen; so people who are the targets of racial hate or of everyday hate or of appropriation, once they start making a noise is when you will see change.”

Kukreja refers to a well-known phrase: “‘One mosquito can disturb the sleep of a big person,’ so, we just need a whole army of small mosquitoes to disturb the kind of racial sleep of the dominant group and make them realize that what’s happening is wrong, it’s a very problematic thing, and it’s going to be increasing in Canada, because what happens South of our border always percolates here.”