Content warning: article contains discussions of sexual assault.

In Bero, a small village in Jharkhand, India, a 13-year-old girl weaves her hair into two braids adorned with bright orange ribbons. We see her walking the streets of her village, and at home with her family, yet because of what’s happened to her, she is kept anonymous.

One night, on her attempt to return home from a wedding with some friends, she was dragged into the woods. This young girl was raped by three men, including her cousin. Speaking to camera in the To Kill a Tiger documentary, her father recalled being alarmed when he learned what happened to her. When the news of the crime spreads through the village, locals offer a shocking solution.

“Why not marry [her] to one of the men [that raped her],” says one of the villagers. Though marrying a victim to their abuser to protect a family’s reputation is common in this community, Ranjit cannot imagine doing such a thing to his daughter. That’s when documentary filmmaker Nisha Pahuja shifts focus to Ranjit’s mission to find justice for a crime that occurs, on average, 86 times per day in India.

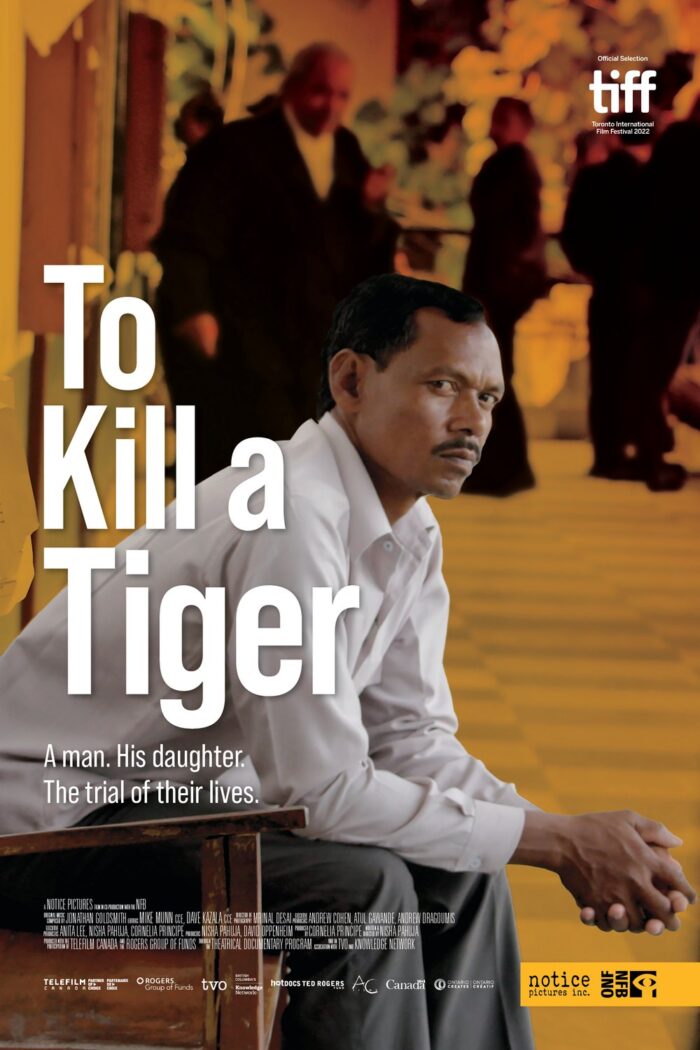

In To Kill a Tiger, Pahuja, an independent Canadian filmmaker born in New Delhi and raised in Toronto, explores rape culture and a justice system that fails India’s women and girls through the story of Ranjit and his family. Though the film focuses on one case in a small village, it tells a bigger story about breaking down the stigma and systemic barriers surrounding sexual assault in South Asian culture and beyond.

The film follows Ranjit and his wife, Jaganti, as they struggle to find justice for their daughter. Starting from 2017, the process spans just over 14 months with numerous court dates, follow-ups with lawyers and authority figures, and both mental and financial burdens. Working with the Srijan Foundation, an India-based human rights NGO, Ranjit and Jaganti were adamant in ensuring their daughter’s voice was heard and not brushed aside like many other cases similar to hers.

In India, more than 46,000 cases of rape were reported to police in 2021, and cases have less than a 30 per cent conviction rate—numbers that reflect a patriarchal society with deep issues of classism, casteism, and sexism. In To Kill a Tiger, we see these systemic barriers to justice from villagers holding the notion that ‘boys will be boys’ as an excuse for their actions as well as the Initial Officer assigned to the case handing over the file to the Investigating Officer who did not do his job properly.

“In a lot of South Asian cultures, if you don’t talk about the problem, then it doesn’t exist,” Sumaya Karimi, a social worker at the Khalil Centre, tells RepresentASIAN Project. This silencing, and its impact on women and girls, is what Pahuja expertly displays in To Kill a Tiger—and what will make it resonate with viewers.

According to a research paper published in the International Journal of Legal Science and Innovation, survivors in India who seek justice face many barriers, such as the pressure from families to stay silent in fear of retaliation and re-traumatization while seeking medical help, especially with protocols like the invasive “two finger test” done by medical professionals. Additionally, survivors are often either told to drop cases or to compromise rather than proceeding with the judicial system.

These issues are also present among the larger South Asian diaspora. Multiple studies that explore the reasons why there is a significantly lower level of disclosure rates with South Asian women living for instance in Canada and the UK highlight cultural norms as a significant factor.

According to a study conducted by British researchers Karen Harrison and Aisha K. Gill, factors that hinder the willingness to disclose and report sexual assault among British South Asian women include “social stigma, rigid gender roles, marriage obligations, expected silence, [and] loss of social support.” Paired with “the cultural concepts of honour and shame,” people tend to shy away from seeking help.

“Being able to open up conversation[s], specifically amongst the [South Asian] population, is the biggest first step that we can do. Connect[ing] with friends and family to unveil that part of ourselves [in saying] this is something that happened, and the more that we’re going to talk about it, the less we’re afraid of it and the less judgement it creates.”

Barna Heer

Barna Heer, a registered provisional psychologist based in Edmonton, Canada, says the way to effectively break down stigmas of sexual assault is to talk about it.

“Being able to open up conversation[s], specifically amongst the [South Asian] population, is the biggest first step that we can do,” Heer tells RepresentASIAN Project. “Connect[ing] with friends and family to unveil that part of ourselves [in saying] this is something that happened, and the more that we’re going to talk about it, the less we’re afraid of it and the less judgement it creates.”

In To Kill a Tiger, Ranjit and Jaganti face these challenges head on, but even with the Srijan Foundation’s support, nothing could prepare them for the backlash they faced. As threats persist, Ranjit and Jaganti start taking turns sleeping throughout the night so someone is always awake to make sure their family is safe. Throughout the film, Ranjit has many conversations with men from the village who are furious with him. The villagers were livid with Ranjit, and viewed the family’s court case—and the involvement of Pahuja’s cameras—as an act of indiscretion, airing out their society’s dirty laundry.

This pushback led to feelings of doubt from the family. “Do you think it’s wrong that we involved the police?,” Jaganti asks Pahuja when feeling the pressure of the villagers’ voices, questioning if Ranjit and herself erred by coming forward.

This type of uncertainty along with self-blame often arises when victims and their families receive a negative reaction from those around them when speaking out on sexual assault. This, in turn, reinforces the silencing of victims, causing them to lose confidence in a their ability to express what they have been through to anyone—a common issue in rape culture around the globe.

“The fact that there’s an unspoken fear [of] someone find[ing] out something like this happened to you. For some reason, [the] special status on whether [a woman is] not a virgin is tied to a family’s honour. There’s much at stake for a woman. If sexual violence [were to occur] it makes sense to not come forward,” says Heer.

In India, a heavily patriarchal society, the magnitude of these crimes is under-reported due to resolving issues without any official authority involvement. The 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder of a young woman, known as the Nirbhaya case, prompted nationwide protests and calls for reform, leading to changes to several laws—but the issue of violence against women remains rampant. The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences, or known as the POCSO was introduced in 2019; a law that recognizes various offences as criminal which are punishable by law. As of 2021, about 50,000 cases were registered under POCSO in India.

“The power of the [To Kill a Tiger] story and the reason it is so impactful is [partly due to the fact that] the idea of misogyny, women’s rights and rape culture [are] not exclusive to India or those parts of the world,” Pahuja tells RepresentASIAN Project.

“The power of the [To Kill a Tiger] story and the reason it is so impactful is [partly due to the fact that] the idea of misogyny, women’s rights and rape culture [are] not exclusive to India or those parts of the world.”

Nisha Pahuja

In 2021, more than 34,200 sexual assault crimes were reported in Canada according to Statistics Canada. Sexual assaults reported to the police have also reached the highest rate since 1996.

There have been several documentaries and films that look at sexual violence in India. What makes To Kill a Tiger standout is Pahuja’s ability to make you feel like you are fighting alongside Ranjit, Janganti and their daughter to bring justice.

The filmmaker contrasts the grisly details of the crime with beautiful cinematography of Jharkhand, India. From the up-close silent car rides to court, to wideshot sceneries of a burning field, Pahuja captures the emotion of each piece of this story, showcasing the sheer determination of this family in a way that will give you goosebumps.

“I feel that this film could have a profound effect on men in India. I’m hoping that more men are inspired by Ranjit, to actually stand by their daughter, and I hope more women and girls are inspired by his daughter to actually seek justice,” says Pahuja.

Being a rice farmer from a small village in Jharkhand, Ranjit and his family’s story is that of an underdog going up against deeply entrenched social norms and refusing to back down.

“Once I was told ‘you can’t kill a tiger by yourself,’” Ranjit says in the film, “But I told them ‘I’ll show you how to kill a tiger all by yourself.’ And I did.”

To Kill a Tiger will be available to Canadian viewers for free on NFB.ca and also broadcasted via TVO and the Knowledge networks this fall. For all other viewers, the film will continue being played at festivals outside of Canada.

Like this post? Follow The RepresentASIAN Project on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube to keep updated on the latest content.