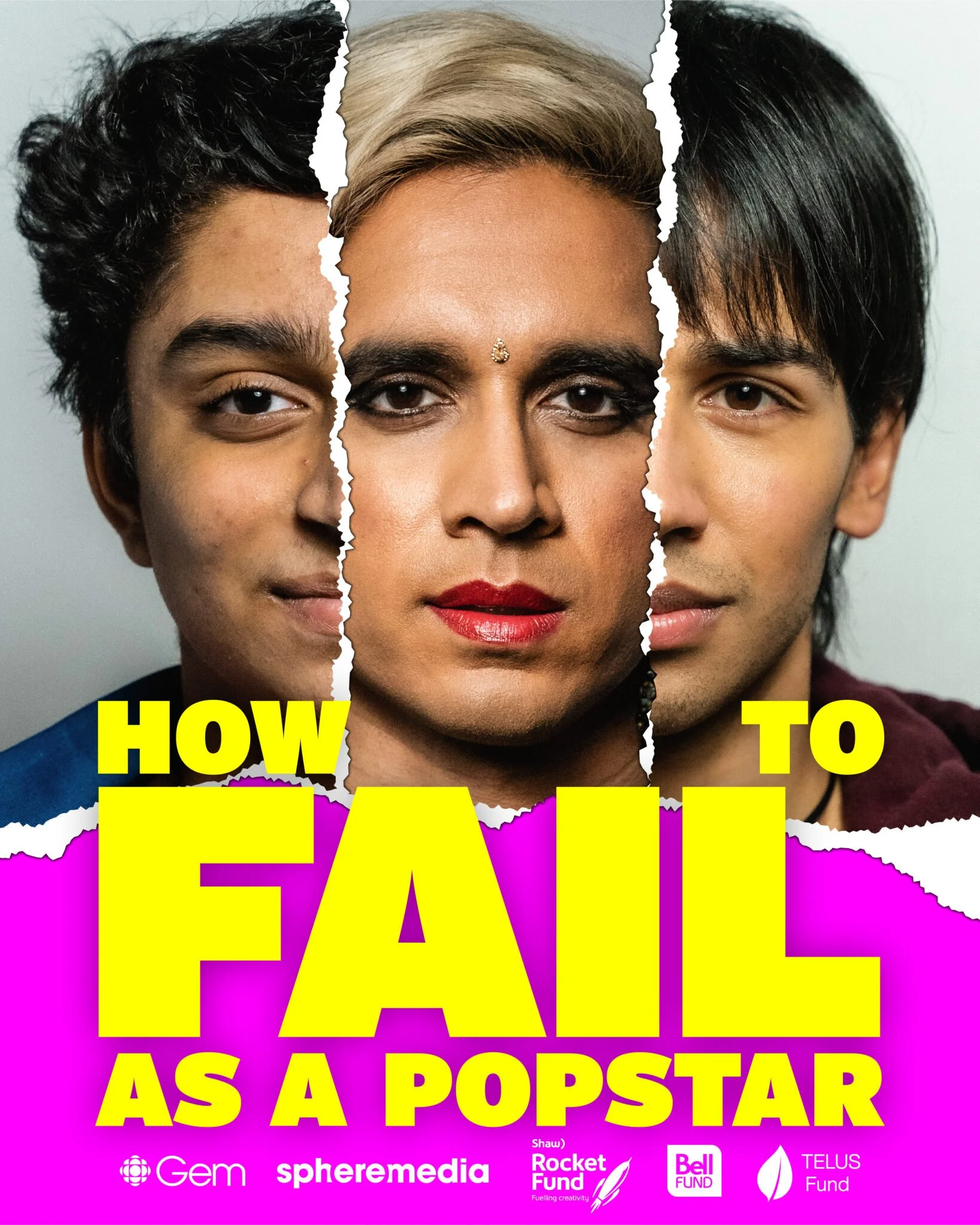

Vivek Shraya On Telling a Queer, Brown Story on Her Terms

The author, playwright, actor and musician is telling her story her way in her new series ‘How to Fail as a Popstar’.

Dream Vivek (Vivek Shraya) sings, in a still from How to Fail as a Popstar. Photo: Karn Sylvestre, courtesy of Sphere Media.

Vivek Shraya has been a lot of things: an author, a playwright, an actor, a musician. But, she’s never been a popstar. Growing up as a “brown, queer kid” in Edmonton, Shraya dreamed of being as big of a pop sensation as Madonna. While she didn’t quite hit that mark, she transformed her life and obsession with pop music into a new series on CBC Gem, How to Fail as a Popstar. The show, written and created by Shraya and based on a one-woman play of the same name, tells the story of Shraya’s journey as she chases pop superstardom—and doesn’t make it.

We talked to Shraya about failure, the pressure on BIPOC and queer creators to represent and the model minority myth.

Photo: CBC Gem.

Popstar’s been in the world for a while now, since 2019. First as a play then as a book. Why do you think the story has continued to resonate?

It’s funny, I was thinking about that this morning. I think part of it is that people are really, genuinely interested in a story about failure, despite the fact that we don’t allow room for it. Maybe that’s exactly why people are interested in it. I do think that there’s something also very universal about it. We’ve all had big dreams, whatever they are. Maybe we haven’t even admitted them to ourselves, and have had to grow out of them in some ways. And I think that’s what people are relating to.

And you’ve transformed your failure into success, in a way.

It’s true (laughs). Me wanting to talk about failure is undermined by the success of the project enduring and getting to do so many things with it. Though, it is interesting: once the show comes out, it will be marked as a success or a failure, depending on how many people view it and how much reach it has and what distribution it does or doesn’t get. It’s a weird meta thing to happen. Right now, it feels like a success because I’ve gotten to do it, but whether or not it gets to be seen as a success is in some ways out of my control.

Vivek (Adrian Pavone) holds Sabrina Nadine Bhabha) as Chandrika (Ayesha Mansur Gonsalves) stands nearby in a still from How to Fail as a Popstar. Photo: Courtesy Sphere Media.

Yeah and with failure and being Asian. You know, the model minority myth—Asians are told they can’t fail. It’s almost revolutionary to me that you’re embracing failure.

It’s interesting you say that! I remember the first time telling my mom I was working on a project called How to Fail at Being a Popstar and she could not compute. She was like, don’t you still sing? Like, aren’t you a singer? And I’m like, yeah, I sing, but like, I haven’t reached the success I wanted. And she’s like, that’s not a failure, as long as you can sing, you’re not a failure. It also made me realize that like, it is kind of ungrateful. For me to fail, I needed to have dreams first. And I couldn’t have had the dreams that I had if it weren’t for my immigrant parents sacrificing and working as hard as they did. It was an interesting and humbling moment with my parents to also remember that I was lucky to dream, and to pursue those dreams.

Aside from failure, tell me about that upbringing as a queer brown kid in Edmonton. What were some of those cultural details you wanted to keep

One of the things I got to keep was that I grew up in a non-denominational religious organization. It wasn’t a typical sort of Hindu environment. I grew up with a guru. I thought that would be something that I’d have to change—I even mentally prepared myself for what that would look like, or what those conversations would look like, but it actually never came up.

The story feels extremely intersectional, extremely Brown, extremely specific. It’s not just a brown kid in Toronto, for instance. It’s a brown kid in Edmonton. How often have we seen stories about brown queer kids from Alberta. Those aren’t the stories that get made—stories about people who have a guru and have a very fashionable mom. There’s so many nuances of what it means to be POC that I love that the show captures. So often the problem with representation is we all become monoliths. It’s like there’s one way to be brown. There’s one way to be queer and again, yeah, the specificity of my brownness. my queerness. My upbringing is very much in the show, which I think is beautiful.

Vivek (Adrian Pavone) with a guitar in a studio, in a still from How to Fail as a Popstar. Photo: Courtesy Sphere Media

I love that the show kind of depicts all sorts of intersecting identities that are never brought up.

As someone who makes media, I’m often thinking about representation. I find it really hard actually, to engage with a queer film, I have to take off my thinking hat and not think about how this is moving the needle forward or backward—same thing with POC representation. I’ve been craving stories about difference that aren’t about difference, where people are diverse but their experiences of oppression or hardship aren’t at the forefront. That’s not to take away from our realities. I think if you’re looking at Popstar, there are definitely examples of racism or sexism and misogyny. But I think sometimes what happens is we’re forced to tell only those kinds of stories. I’ve certainly felt pressure as a queer person of colour to tell those kinds of stories. What I love about the series is that it’s about a brown kid with big dreams. And I think it’s really special that it is it is a queer story, it is a brown story, it is a trans story, but none of those things have to be mentioned, because at all times, Vivek gets to be who he or she is, and the people in his or her life love him and respect him and see him or her in that moment for that person. And I think that’s, that, to me feels like exactly the kind of thing I want to be making in 2023.

“I’ve been craving stories about difference that aren’t about difference, where people are diverse but their experiences of oppression or hardship aren’t at the forefront... I’ve certainly felt pressure as a queer person of colour to tell those kinds of stories.”

I also love that the story doesn’t fall into those typical beats. Like, there isn’t a coming out moment or a stinky lunch moment.

Exactly. There’s no identity crisis. If you dig for those things, you can find them. But that’s not the center of the story. It’s nice for us to get to tell stories that aren’t just about our trauma or our difference.

Why was it so important to you to go beyond those typical story beats?

I’ve just felt really limited by that box. There’s so much storytelling that I’ve wanted to but I’ve just felt really limited by how institutions, granting bodies, audiences have perceived me. A few years ago, I published a children’s book about raccoons. And it’s truly a children’s book about raccoons, like it’s pretty basic. It was one of the hardest things for me to get published and part of why is because there’s such an expectation that because I’m trans or because I’m queer, or because I’m brown, that’s the kind of book I should be writing at all times. But guess what, I have other interests. I have interest in raccoons, I have interest in pop culture. I have interest in you know, Madonna or Beyonce. And so Popstar feels like another step in the right direction for me and the kind of art that I want to make.

I don’t want to dismiss art that is about identity. I’ve made so much of it and I’ll probably continue to make art that talks about social issues. I do feel a responsibility as well as someone with a platform to do that. But I think it’s about choice and agency. It’s one thing if I want to make a story that talks about what it needs to be trans, but iI shouldn’t feel pressured to—and I often do. It was really freeing to expand outside of that. I was deliberate about that from the inception—I remember having conversations with my play director and saying I explicitly don’t want this to be specifically about queerness, brownness, transness. Not because I’m ashamed of those identities, but because I want to be able to show other sides of myself and I want to talk about, you know, Mary J. Blige.

Dream Vivek (Vivek Shraya) wows the crowd at Le Chateau, in a still from How to Fail as a Popstar. Photo: Karn Sylvestre, courtesy of Sphere Media.

My last question before we wrap. What would you want someone like young Vivek to get from this show?

If I was gonna speak specifically to young Vivek… I just feel so much pride in that kid. It’s so easy to be jaded as a 42 year-old artist, like I’ve been through various art industries so I know how things go. But that kid had no idea the odds that were against him.. and yet he was so fearless and driven and ambitious, and I’m probably projecting a little bit but I missed that innocence.

If I could go back in time, I probably wouldn’t change anything, I wouldn’t tell him not to do it because in the end, that love for music has brought me here and now I’ve gotten to do a whole show about it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How to Fail as a Popstar is streaming now on CBC Gem.