How Avant-Garde Visionary Wu Fei Fell in Love With Her Parents’ Dream

Through her innovative spirit and commitment to transcending boundaries, the guzheng player is redefining the possibilities of music.

Wu Fei. Courtesy photo

It may be hard to believe, but Chinese musician Wu Fei—a true triple-threat who is a master composer, singer and instrumentalist—never dreamt of making music for a living, or really, even as a pastime. As so many Asian folks can relate, it was her parents’ dream.

An only child, Fei was born just after China’s Cultural Revolution, and so her parents were keen to do all they could for her, ensuring a promising future. That meant music lessons and competitions from an early age, along with performing at large-scale venues like the Beijing Concert Hall, the Beijing Children’s Palace and the Great Hall of The People (which seats an intimidating 10,000 audience members).

“My parents were the first generation of young parents who, during the Chinese reopening, thought, ‘Let’s put everything behind and be ready to thrive, and to be embraced by the world,’” says Fei. “[Because of the] one-child policy, for the first time in our contemporary history, girls were encouraged to be raised just like boys. My parents, they had their own dreams taken away when they were young, so they put their dreams on me.”

That’s why Fei was only two years old when she was selected to be trained as a professional musician—her parents started her early. But, training a child to learn music aside, it wasn’t a simple process. During the Cultural Revolution, many music manufacturers were banned from making instruments, and traditional Chinese instruments were considered “evil.” As a result, much of what was left had been burned or hidden, making it tough to find anything when Fei was little.

“My parents, they had their own dreams taken away when they were young, so they put their dreams on me.”

But her mother was resourceful and visited the Beijing Music Factory to see what had survived and not been tossed out. She discovered the 2,000-year-old guzheng, a traditional 21-string Chinese zither with origins in the Middle East, having come to China through the Silk Road trade. It was cheap, “almost free,” and not a common instrument at the time, making it the perfect option for a young Fei to learn and stand out. By mere circumstance, the guzheng would become Fei’s signature. But it was a difficult road. At just age five, she would begin taking lessons, and was forced to train, at minimum, two hours a day for the next 10 years, leading to a “complicated, intense” relationship with music.

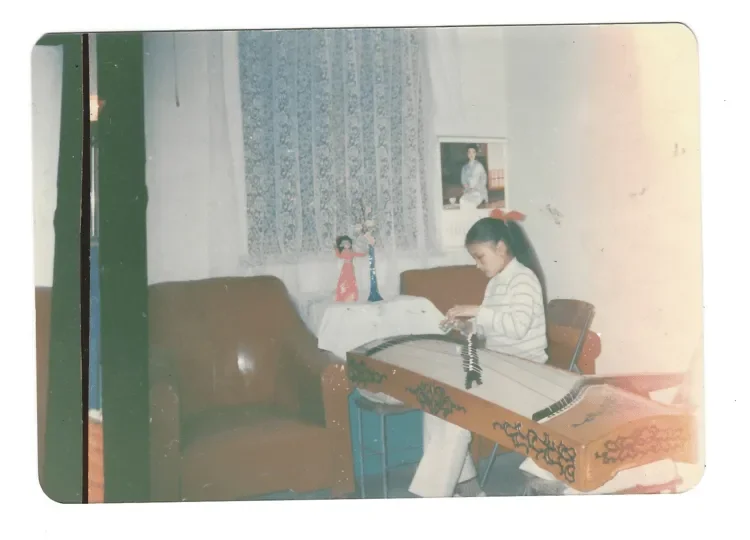

A young Wu Fei playing the guzheng. Courtesy photo.

After completing her formal music education at the China Conservatory of Music, Fei moved to California, where she earned a degree in composition at Mills College. There, she also studied under influential composers such as Fred Frith and Pauline Oliveros, whose experimental approaches helped shape her artistic philosophy which often sees her intertwining different cultural styles of music.

It was during this time of exploration, in discovering everything from West African drumming to Central Asian jazz, that Fei began to finally find her own joy for the art. She witnessed the culture of “jamming,” and how music can bring communities together and bring people to life; “it liberated me,” says Fei.

It helped, too, when one of her professors acknowledged her sharp skill, but said he couldn’t hear her in her performances. It was a “traumatizing” moment for Fei, who didn’t realize music could go deeper, but also didn’t know why she made it. She took a week off at the time to consider her goal: “I’ve been put on this path since I was a toddler and have been writing music my entire life—to meet others’ expectations … but not my own.”

“I’ve been put on this path since I was a toddler and have been writing music my entire life—to meet others’ expectations…but not my own.”

Her professor suggested she do away with the structure that had been so deeply ingrained, and to instead try experimenting and improvising, and letting her heart guide her.

“I was in a very small but a very safe environment with all my colleagues and friends, so I felt free and I didn’t feel judged,” says Fei. “The Chinese culture can be very heavy—it’s beautiful, there’s a lot of wisdom, but there can be a lot of pressure. I felt like I had a pair of wings, but I never flew. I felt stuck. At 20-something, I wondered, do I change [my] profession? I told myself, you know what, here’s the sky, I should test my wings before I give up. And then I just took off, I thought I was going to die, but I have to try.”

Courtesy photo.

Charming as ever, Fei laughs through the memory, though it’s clear it was a life-changing epiphany. And, spoiler alert: she did not die. In fact, because of that one moment and the permission she found to break her own boundaries, all these years later, her music has come to transcend genre, blending traditional Chinese folk, classical music and avant-garde improvisation with Western contemporary influences like free jazz and experimental soundscapes. Her performances often feature dynamic interactions between the guzheng and unconventional elements, like electronics, and unconventional instruments, resulting in a sound that is uniquely her own.

As Fei puts it, most artists arrive at a stage where, like Picasso, you realize the role of a great artist is to break all the rules, not follow them. For a musician whose foundation was built on those rules through over 10,000 hours of training, it’s not easy to break. So Fei continued to travel, discovering new and old traditions, educating herself on how limitless music can be.

Although her Chinese heritage gave her her dream and her instrument, now, a defining feature of Fei’s artistry is her ability to bridge cultural and musical divides. This is exemplified in her collaborations with international artists, including American banjo master Abigail Washburn, with whom she created Wu Fei & Abigail Washburn, an album that impressively integrates Appalachian folk and Chinese traditional music. The project highlights the surprising similarities between two seemingly disparate traditions, underlining Fei’s talent for finding common ground through sound.

Fei has performed at prestigious venues and festivals worldwide, including Beijing’s Forbidden City, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Paris’s Quai Branly Museum. Her compositions have been commissioned by everyone from the Carnegie Hall Weill Music Institute to the Kronos Quartet, further establishing her as a pioneering force in contemporary music.

This February, she will be gracing Toronto, as a featured performer in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s Year of the Snake concert at Roy Thomson Hall. It’s a full-circle engagement.

“It feels like a childhood dream coming true,” says Fei, with a grin. “Since I was a child, I would sit in front of the TV watching New Year’s concerts while helping my parents make dumplings. Since I was a music kid, I thought, ‘One day, I’ll be on that stage.”

Through her innovative spirit and commitment to transcending boundaries, Fei continues to redefine the possibilities of music. Her work not only preserves the legacy of the guzheng but also propels it into the future. It’s a weighty legacy, one that began from a very young age.

Today, when asked why she makes music, Fei has this to say: “I literally can’t stop.” In other words, after all this time, it’s become who she is. She hears things others can’t—the “white silence” in the wait for a train, the pitch of a dripping faucet, the relentless “B flat” of air conditioners in North American hotels.

“Everything is a song to me,” she adds. So why not embrace it?