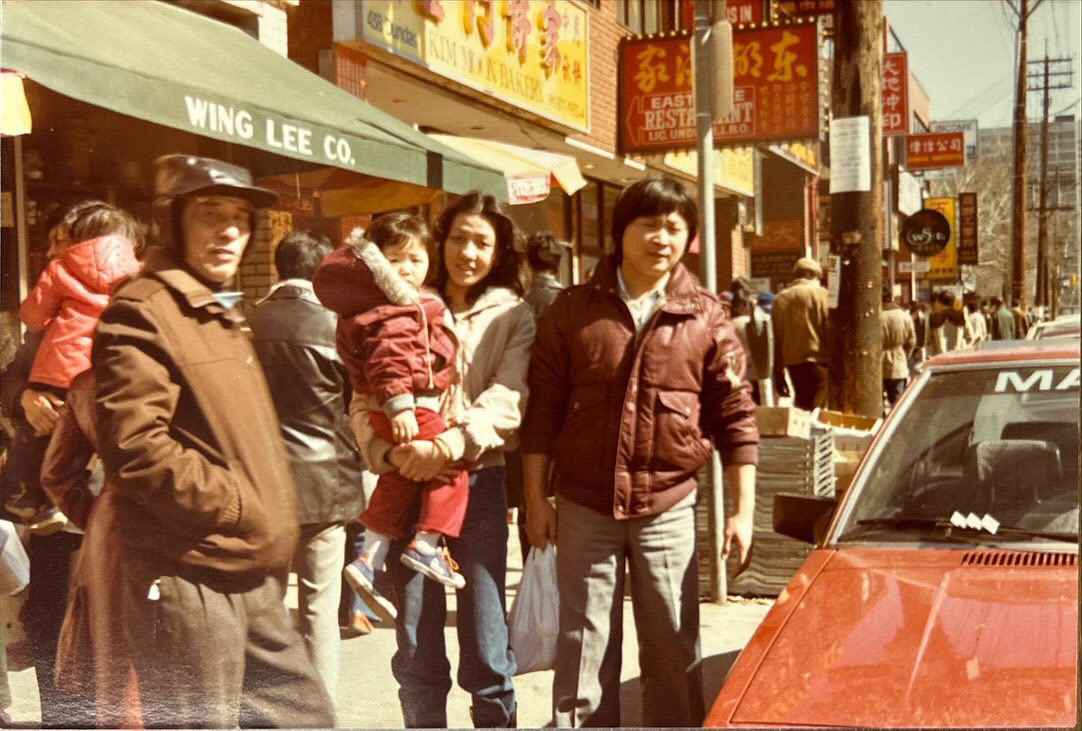

When husband and wife Michael Liu and Mei Wang first opened up their restaurant in 1986, it was somewhat of an accident. The Liu family moved to Canada from India in 1981, settling down in Toronto. At the time, Wang was working as a receptionist at a hospital while Liu worked in a factory. But during a family dinner outing, one of the owners of the old Yueh Tung restaurant happened to be dining at the same spot and got to talking with the couple. Eventually, they decided to go into business with the family

“That’s how it all started,” recalls Jeanette Liu, Michael and Wang’s daughter who now runs the front-of-house at Yueh Tung.

At first, it was incredibly tough: Liu, who ran the kitchen, and Wang, who ran front-of-house, didn’t know how to manage a restaurant. Another couple that had partnered with the Liu family to run the place quit because of the disorganization.

“My dad said that they threw the keys on the table and told him, ‘I’ll give you another week until your business shuts down,’” says Jeanette. “And, well, here we are almost 40 years later.”

Indeed, the Lius didn’t give up. To get diners in the door, Liu began selling lobster super cheaply. The lobsters, which were big and affordable compared to other downtown Toronto restaurants, became a hit. And while Yueh Tung only served Cantonese food at first, which was the most well-known Chinese food in Canada at the time, the Lius soon began to introduce Hakka dishes to the menu to pay homage to their family history as Chinese people living in India.

One important note: “Hakka food” is a slight misnomer. While there is a group of people in China called the Hakka, “Hakka cuisine” – like what’s served at Yueh Tung – has its own culinary history. The product of Chinese migrant workers and their descendents living in India, Hakka dishes use Indian vegetables and spices alongside Chinese sauces and cooking methods like stir-frying.

At the time, however, Canadian diners were unfamiliar with Hakka.

“Downtown Toronto wasn’t as diverse as it is today,” Jeanette says. “They were aware of maybe greasy Chinese food, like chicken balls, fried rice, that sort of thing.” But Hakka staples, like chili chicken, were totally foreign. In fact, Jeanette believes that Yueh Tung was the first Hakka restaurant in Canada, if not North America.

To account for the difference in palette, Jeanette says that her father made certain modifications on Hakka dishes. For example, he used cilantro and ginger to create a more herb-y tasting Manchurian chicken dish that became popular with Canadian diners who couldn’t handle the spiciness of many Hakka dishes.

And, to get inexperienced diners interested in Hakka food, Jeanette says that her dad would stand outside the restaurant handing out samples to passersby. And it worked: the Lius steadily built a dedicated crowd and, soon, the dining room was completely full with eager diners lining up for tables.

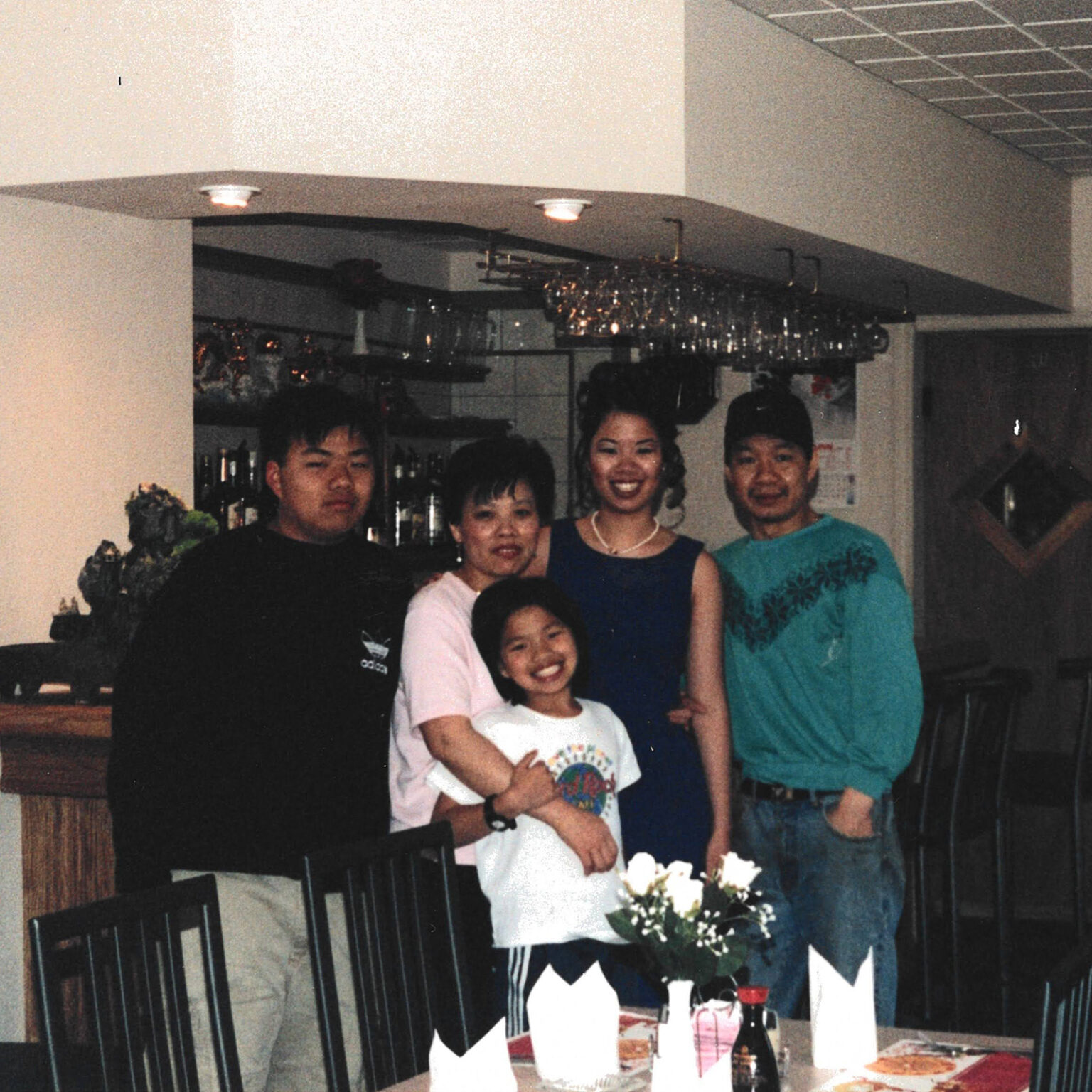

Then came Liu’s health problems. In 2010, he suffered a heart attack. Jeanette’s sister Joanna, who was always a passionate foodie, stepped in to help in the kitchen after returning from university—under Liu’s supervision. But then Liu had a stroke in 2012 that affected his mobility and required more recovery time. Joanna, who Liu said “couldn’t cut it” in his restaurant, obtained a culinary diploma from George Brown and stepped up as head chef at this time. Soon after, Jeanette, who was working as a reporter in Alberta, also came home, to help run the front-of-house. The sisters, who had casually worked in the restaurant their whole lives, were now running the whole business.

“Parents never intend, especially in Chinese families, for their kids to take on the restaurant business or work in the kitchen,” Jeanette says. “It was seen as a means to an end, just to support their family.”

But the sisters made a good team. The restaurant was busy, the small upgrades they made to the dining room and menu were well-received and Liu, who had luckily regained his mobility and strength, was back in the restaurant chatting with old regulars.

Still, the sisters have dealt with their fair share of hardships: shrinkflation has made the cost of all their ingredients skyrocket (Jeanette says that what used to cost them $20 now costs well over $90), rent has gone up, their customer base of downtown workers now work from home and their old regulars are now too elderly to climb the stairs up to Yueh Tung.

The worst hit of all, however, came during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jeanette recalls anti-Asian rhetoric and misinformation online surrounding how COVID spread. “I saw messages from people I knew saying ‘don’t go to Chinese restaurants, you’re going to get sick and catch COVID,’” she says. Business slowed down at this time and Jeanette, on maternity leave, watched as her mom and sister tried to keep the restaurant afloat as anti-Chinese sentiment and pandemic-induced closures led more diners away. She adds, “Business was hit really fast, really drastically, really hard.”

Despite the challenges, though, Jeanette and Joanna are determined to keep Yueh Tung open, a testament to what their parents built. As she watches the Chinatown mainstays shutter (like Goldstone Noodle, which closed this summer after 30 years in business), Jeanette says that she’s honoured to carry on her parents’ legacy.

When the Liu family visits other restaurants around Toronto and sees Liu’s recipe for Manchurian Chicken served, they’re proud of the stamp they’ve put on the city’s culinary scene.

“The younger chefs, they’re gaining a lot of notoriety, but it was the older generation that really brought authentic food to the city and they never got to experience the accolades,” says Jeanette. She hopes that, one day, when her parents come to visit Yueh Tung, they’ll be welcomed with a packed dining room and the bustling business that they enjoyed when they ran the show.

“I think the legacy of Yueh Tung, for us girls, is to carry on what our parents started,” Jeanette says. “We want to respect what they created: a place for our community and city to gather and learn about a different culture through food. And we hope to continue to bring people together and serve them good, delicious food at affordable prices.”

Like this post? Follow The RepresentASIAN Project on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube to keep updated on the latest content.