Thi Bui: Cartoonist, Author, ‘The Best We Could Do’

On why ‘The Best We Could Do’ is an “accidental memoir” and how she came to terms with her Vietnamese culture as an Asian-American.

Thi Bui. Photo: Andria Lo.

They say history is written by the victors, but Thi Bui believes you don’t have to accept everything you hear.

The public high school teacher turned cartoonist is the creator of The Best We Could Do, a deeply moving graphic memoir that explores her family’s journey from Vietnam to the United States in the 1970s.

Growing up in San Diego, Calif., Bui was always deeply aware of the stereotypes her culture faced in America. But one of her biggest gripes was with how American history portrayed Vietnamese people and the Vietnam War. That’s why the 44-year-old created her book.

Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.

“[I wanted to] reset the power balance and use my voice to stand up for all the voices that had been shouted over for so long by mostly white American men making movies and books,” she said.

Stories about immigration and refugees are not often highlighted in pop culture. Not only is this because “they’re depressing,” said Bui, but also because “immigrants and refugees are some of the least powerful people, especially when they’re newcomers. So they’re not in the position of telling their own stories most of the time.”

Despite this, these stories are highly relevant today, especially considering the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis and fears associated with this group of people.

“I’m hoping that people come away [from my book] with more empathy and a greater openness to look at people more deeply before they decide who they are,” the cartoonist said.

Read on to find out why Bui calls The Best We Could Do an “accidental memoir” and how she came to terms with her Vietnamese culture as an Asian-American.

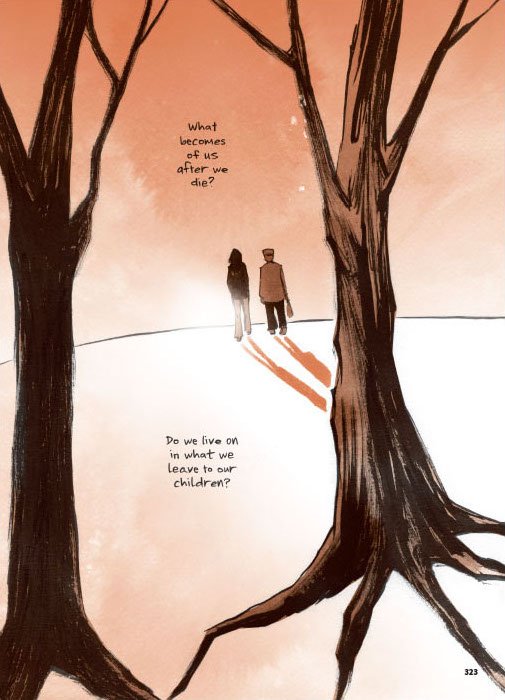

An image from The Best We Could Do. Photo: Courtesy Thi Bui.

On starting a career in comics

I was [always artistic]. I always drew and then I kept drawing. I was actually an art major in college. But the type of drawing that you learn in school is from observation and it’s way more than you need for comics. So I actually had to unlearn all of that training and learn a shorthand way of drawing that works better for something where you have to draw the same people over and over again in different poses.

On the inspiration behind her graphic novel

It was an accidental memoir. It wasn’t supposed to be about me. It was supposed to be a vehicle for me to figure out all of these questions that I had about who I was, where I came from, and how I ended up growing up here in the U.S. so far from where I was born. I was trying to understand all those forces that cause a family to uproot themselves and go to the other side of the world, and so for me, it was necessary to go into the Vietnam War [in my book] because that’s a huge part of my origin story.

It was [also] a representation issue. I was contending with a lot of stereotypes of Vietnamese people from all the movies that are out there about the Vietnam War made by Americans. So I felt like if I wrote anything in prose, I would still have to deal with these stereotypes that are long-lasting and really affect people’s biases. So I had to replace them with images I made.

“[My graphic novel] wasn’t supposed to be about me. It was supposed to be a vehicle for me to figure out all of these questions that I had about who I was, where I came from, and how I ended up growing up here in the U.S. so far from where I was born.”

On coming to terms with her Vietnamese culture

[I grew] up with the confusing idea that there could be parts of me that were Vietnamese and parts of me that were American. I didn’t understand how that would work. I had access to American culture, but I didn’t really have access to Vietnamese culture except for what was presented to me as Vietnamese by people my parents’ age. That was hard for me to buy. If I was in Vietnam, I don’t know that I would particularly enjoy ribbon dancing or fan dancing, but this was what was offered to a young Vietnamese girl in the States. So it took me a little while to figure out — especially after going back to Vietnam on my own terms [in my early twenties] — that oh, my culture is a more dynamic thing and you can pick and choose what parts of a culture connect with you.

Thi Bui. Photo: Andria Lo.

On feeling disconnected from immigrant parents

I think maybe the disconnect has to do with the lack of intimacy that comes from your parents not being able to talk to you about these life-changing experiences that they went through. They think you won’t understand or the context is too different or you just don’t ever ask them about it. When you’re missing a huge part of somebody else’s experience, I think the void that you’re feeling is that lack of intimacy even if you love each other.

“[I wanted to] reset the power balance and use my voice to stand up for all the voices that had been shouted over for so long by mostly white American men making movies and books.”

I think [my mom found it easier to talk to my husband about her experiences because] he was like a neutral blank piece of paper. There’s no assumed prior knowledge. There’s no baggage between the two of them like there is me. She would often say, “Oh, you were born there. You know how it is” and I wouldn’t know how it was. I wanted her to explain in complete detail, so it was just easier for her to tell someone who didn’t know anything.

Relative to other Asian parents, especially Vietnamese refugee parents who have gone through traumatic situations, I actually think [my parents] talk a lot and that’s why I did the book — because I had access.

On how her book brought her family together

Closeness is a tricky thing. It just slips through your hands; it’s hard to hold on to it. But while we were working on[the book], it was a sneaky way of spending a lot of quality time together.

When I showed [my family] rough drafts of the chapters, it would help them remember more stuff. So they got really into it. They became collaborators. I think involving them before the book was done and in print was good because it made them trust the project more and also helped me make it a better book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.