Being Fetishized or Othered Shouldn’t Be the Only Options for Asian Women

The Atlanta shootings have made one thing clear: racial stereotypes can have lasting impacts and can be deadly.

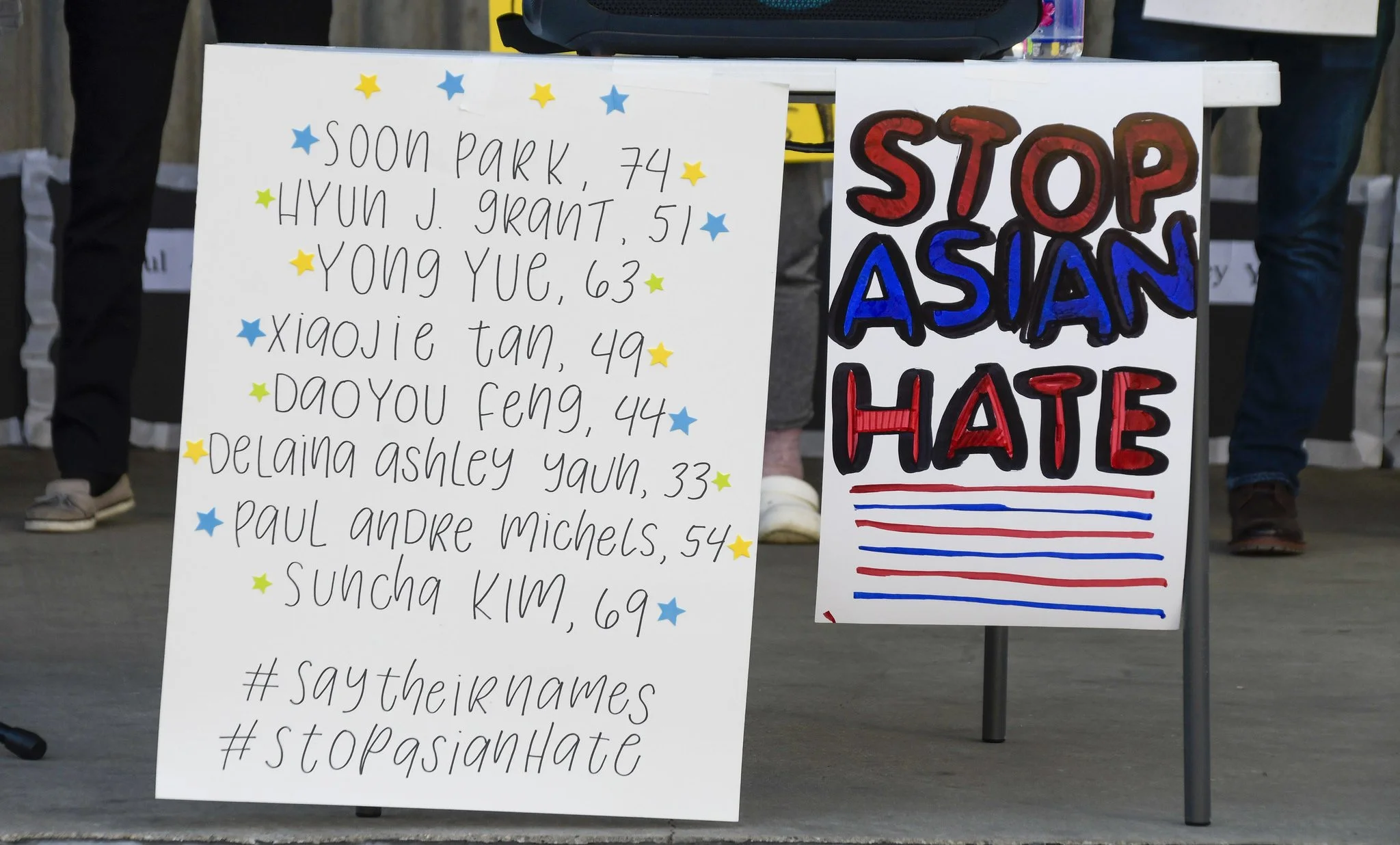

Sign from a rally and vigil at Rosa Parks Circle in downtown Grand Rapids on Saturday, March 20, 2021 to denounce the murders in Georgia days after, six Asian American women and two other men were killed in a mass shooting at three Atlanta area spas. Photo: John Rothwell.

I’ve been struggling a lot these past few days to process the Atlanta shootings. The first time I heard what happened, my heart broke. Eight people — six of whom were Asian women — were killed by a white gunman in a series of attacks at three massage parlours.

By now, everyone’s heard the story. But the day the news broke, I couldn’t bring myself to go online. Every time I saw news about the incident pop up on my feed, I cringed and looked away. The truth is I was sad, angry and distressed, but I pushed those feelings away partly because I thought I was being too sensitive, partly because I didn’t want to deal with this trauma on top of a pandemic, and partly because I didn’t think the world would wake up to the blatant racism.

But to see so many people, celebs and regular folks alike, speak up about what’s happening has made me feel less alone and proud that people are calling it what it is. It’s also made me feel brave enough to share my own story.

I was 19 the first time a grown man called me “Lucy Liu” at a bar. I didn’t know him, but I knew what he was implying. He was sexualizing me — something commonly done to Asian women in pop culture.

I cringed when I heard this. Some may have perceived the name reference as a form of flattery, flirting even, but to me, it came off as ignorant and misinformed. Liu and I are both Chinese, have almond-shaped eyes and long, dark hair, but that doesn’t make us synonymous. Unfortunately, that hasn’t stopped people from calling me by the actress’ name or understanding the implications of doing so.

Growing up in a predominantly white town, I was well aware that being Asian had certain associations, and Lucy Liu was one of them. She brought mainstream visibility to East Asians in North America, but her roles were perceived by Hollywood and the public in a very specific way.

If she wasn’t the dragon lady, she was the martial artist and always, always hypersexualized.

I’ve been called “Lucy Liu” on plenty of occasions in my early 20s — a time when Liu was the only well-known Asian actress in Hollywood. But the first time it happened was the most memorable because it was also the first time I went from being perceived as the “cute, quiet Asian girl” to “exotic Asian woman.”

These racial stereotypes have lasting impacts and, as we’ve seen with the Atlanta shootings, can be deadly. As Audrey Yap, a University of Victoria professor of feminist philosophy, told Buzzfeed News: “People sometimes seem to think that treating Asian women as exotic sex objects is somehow a compliment for us, when it’s actually something that contributes to violence against us.”

For me, being called “Lucy Liu” was a subconscious reminder that these racial stereotypes are all I am and all I’ll ever be perceived as because of the portrayal of Asians in pop culture. I know representation won’t solve racism, but I strongly believe representation is key to correcting people’s perceptions of other races.

The phrase “representation matters” has been thrown around so much over the past few years that it may have lost some meaning, but I’m here to remind you that representation STILL matters today and every day. Your voice and your experience, no matter how different, deserves to be heard, shared, and acknowledged. Don’t let anyone tell you that you don’t matter.

I spent most of my youth struggling with my Chinese-Canadian identity because of the lack of Asian representation in my town and in the media. Like so many other Asian women, I’ve had plenty of racist comments thrown at me, both directly and indirectly, which either fetishize or other me.

“My friend told me to date an Asian woman because she’ll treat me right.”

“Does she even speak English?”

“I’ve never been with an Asian before.”

“How do you put in contact lenses?”

Being fetishized or othered shouldn’t be the only options for Asian women. We are more than our racial stereotypes, and we deserve respect.

Isabelle Khoo is a freelance writer and editor. She’s previously worked for big brands like HuffPost Canada and has written about every topic imaginable. From Asian representation to parenting trends to mental health, she’s covered it all. When she’s not busy chasing a story, you can find her boxing or planning her next travel adventure.

P.O.V. is a place where the Asian community can voice their views and perspectives on topics that matter most to them. Interested in contributing? Email us at stories@representasianproject.com.

Supports and Resources

To Report Anti-Asian Hate Crimes in Canada:

Mental Health Resources

The Colour Project — anonymous text-based peer support for mental health with trained volunteers

Subtle Asian Mental Health — private online community for peer support

Donate

Red Canary Song — grassroots collective of Asian and migrant sex workers, organizing transnationally

Butterfly Asian and Migrant Sex Workers Network (Toronto-based)

SWAN Vancouver — culturally-specialized supports and advocacy for im/migrant women engaged in indoor sex work

Hyun Jun Kim GoFundMe to support the victim of the Atlanta shooting’s sons

Additional Tools and Resources

Amplify Asian Voices | Readings + Resources created by Jezz Chung

Project 1907 — Vancouver-based grassroots organization helmed by Asian women and dedicated to elevating marginalized voices.